Besides URLs and short text snippets, which contain news events, opinions and references to others, Twitter is full of visual content.

Twitter-users in Mali decorate their profiles with photos, videos, infographics, documents, and memes to communicate their perspectives on pressing issues. A key aspect of the visual imagery is its reflection on trouble and conflict, which, at times, its tweeters also risk to reinforce.

In this commentary, I discuss the significance of memes on Twitter in Mali. I demonstrate how these humorous images have political and strategic significance, because of the hateful and misleading discourses that can be witnessed through memes. Tweeters use the meme format and hereby spread fear and instil hatred towards specific political actors and groups. In the context of Malian Twitter, these bite-sized images contain tendentious information. The dominant topics covered in memes include jihadism, violence, and foreign military operations.

A sense of belonging

Biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word ‘meme’ to label the cultural variant of ‘gene’. According to Dawkins memes were cultural ideas that had the potential to go viral due to imitation (Dawkins 1976). Anno 2022, memes indeed go viral on digital media. Memes are textual, visual, or aural digital artefacts that display political ideologies and humour.

Meme makers create against the backdrop of local and global events and thus these artefacts are media products of particular societal and cultural conditions. Memes are intertextual. Meaning, they correspond to one another or to particular cultural information. Therefore, interpreting, consuming and producing memes requires prior acquaintance. It is for this reason, that memes facilitate a sense of belonging (Gal 2018, 529). People participate in a particular online culture, shape public discourse and strengthen collective identities by consuming and producing memes (Al-Rawi 2021, 277). Studying frequently shared memes is thus meaningful to make sense of online communities and to pinpoint dominant ideologies and public discussion.

From humor to rumor

During conflict memes can become forms of dark satire. In these conditions, people increasingly produce weaponized and violent memes to support their political agenda (Antinori 2021). As many know from alt-right memes of Pepe the Frog, people exploit memes by using familiar symbols, ironic characters, or cultural references to banalize or normalize violence and express hatred or fear.

Above all, during periods of unrest, memes are fertile ground for the deliberate and intentional spread of false information (disinformation) or the spread of incorrect or misleading information (misinformation). People can use these digital cultural units to interpret war events, communicate political ideologies and narrate biased notions of truths. In this case humor becomes rumor or worse, memes become a type of disinformation called ‘memetic warfare’.

The term ‘memetic warfare’ refers to a form of information warfare, wherein people try to take control of a dialogue or disrupt their enemies. This warfare involves the spread of false messages on social media by using the format of a meme. Since audiences understand its format and its meta-language, they can be easily persuaded into certain narratives about war.

On Twitter in Mali, some of the available memes fit the category of memetic warfare. The makers present manipulative facts to mock, insult and stir collective dislike of the ‘enemy’. The online communities either troll the French, Barkhane and president Macron, or jihadist groups ISGS (an Islamic State affiliated group) and JNIM (an Al-Qaeda aligned group) and their (former) representatives Abu Walid Al Sahraoui and Iyad Ag-Ghaly.

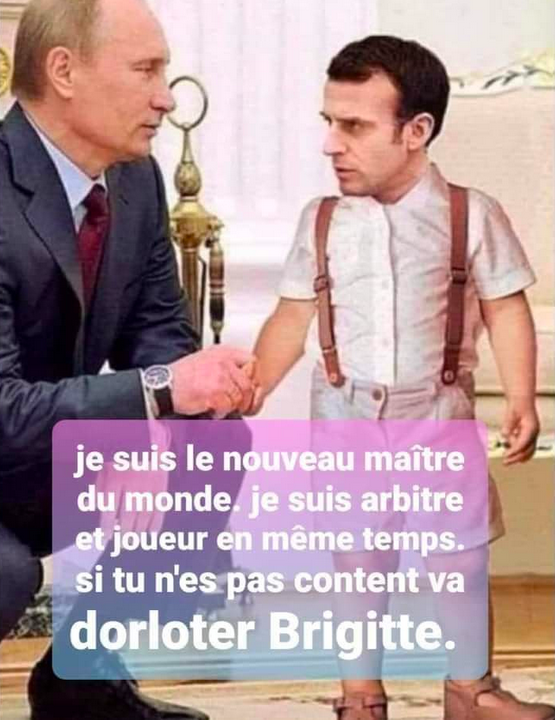

Image 2

Image 1

Take the two memes above. The fact that both use the same imagery shows how Twitter cultures develop and correspond to earlier memes. On the left Vladimir Putin is dressed up in a suit, on the right French president Emanuel Macron is dressed up as a child in a presumably typically French outfit. Macron is belittled, not only by his physical portrayal, but also by the accompanying words that are supposedly Putin’s (image 1): “Come one, little boy, leave the grown-ups be and go play in your room” and (image 2) “I am the new master of the world. I am a referee and a player at the same time. If you’re not contempt, go pamper Brigitte (Macron’s wife)”.

Here, tweeters meme-ify the leaving of Barkhane and the French ambassador and the arrival of Russian mercenaries Wagner in Mali. They make use of stereotypes to negatively stigmatize the French and Macron and positively stigmatize the Russians and Putin. The implied sentiment targets violence and activates hate speech towards the French. The tweeters of this meme artificially shape narratives, namely that Russia is a much more adequate fighter than France, and hereby keep the conflict alive online and disrupt the trust between citizens and military institutions.

Similarly, the above meme ironically highlights the heroism of Wagner, as opposed to the cowardice of ex-colonialist French troops. Like before, this is a dramatized example of memetic warfare, because the maker strengthens the idea that Wagner, in cooperation with FaMa (Malian Armed Forces), is progressing the fight against terrorism in Mali, while France failed doing so.

Similarly, the above meme ironically highlights the heroism of Wagner, as opposed to the cowardice of ex-colonialist French troops. Like before, this is a dramatized example of memetic warfare, because the maker strengthens the idea that Wagner, in cooperation with FaMa (Malian Armed Forces), is progressing the fight against terrorism in Mali, while France failed doing so.

Yet, there is no factious proof for the greater support of Russians to ease the Malian conflict. People who retweet and remake these memes sympathize with the war in a way that is also advocated by the military regime through propaganda narratives. Namely, that they do not need Barkhane in order to fight terrorism in Mali.

Feelings of opposition

The fierceness and brutality of the military regime is also presented in the meme below with at its left president Assimi Goïta and on the right Emmanuel Macron. A Twitter user attached this meme to a text in Arabic about the cancelled trip by the French president to meet the Malian president. The maker of the meme shows how Goïta embarrasses Macron by defeating him in a boxing match.

In the comments on this meme, people laughingly and supportively responded to the purposed reaction by Goïta. Meme sharers invite others to laugh away cruel everyday situations and hereby bring an online community together. But, while memes are creative visual examples of how people in conflict connect, the content format also risks triggering inflammatory reactions and social disharmony. Both makers and consumers of memes use the visual format to promote their ideologies and visions. They come to define conflict and affiliate themselves with- or oppose themselves to particular groups in the conflict. Memetic warfare may thus have harmful effects.

In the comments on this meme, people laughingly and supportively responded to the purposed reaction by Goïta. Meme sharers invite others to laugh away cruel everyday situations and hereby bring an online community together. But, while memes are creative visual examples of how people in conflict connect, the content format also risks triggering inflammatory reactions and social disharmony. Both makers and consumers of memes use the visual format to promote their ideologies and visions. They come to define conflict and affiliate themselves with- or oppose themselves to particular groups in the conflict. Memetic warfare may thus have harmful effects.

This is especially the case due to the misinforming or tendentious narratives that dominate Twitter. Memes are either based on misleading information or the makers focus on some facts and downplay or ignore others. Through stigmatization, stereotypes and a reliance on emotion, they manipulate the public conversation and further the information disorder.

Such is the case with the below examples. These two memes followed as an immediate response to Macron’s call to ECOWAS (CEDEAO) to take appropriate decisions in light of the sanctions towards Mali. According to him, the military led government who recently postponed elections is illegitimate and violent. Moreover, he argued that with the junta’s suspension of news channels France24 and RFI, the sitting government officials deny a freedom of press.

In line with the reaction from Malian authorities, some Twitter users accused CEDEAO of being kept under control by imperialist forces. The Malian Twitter users did not meme-ify the role of the Malian authorities. Instead of ridiculing the national suspension of media or mentioning the violence of military authorities, they chose to ridicule the CEDEAO and France and portrayed these institutions as opportunists, terrorists, and unwanted partners. Hereby the meme makers constructed narratives and created evidence to testify antipathy and fuelled the hatred towards certain groups.

Besides causing an information disorder, memetic warfare can also coincide with conflict in action. For example, the accounts that shared the above memes called for demonstrations against the French.

In the Malian context the action is especially tangible when it comes to ‘terrorism’. Malian Twitter users also make memes on jihadism. In these visual imageries they make fun of the battles between different jihadist groups, their unorganized vandalism, failure in other regions, and supposed savagery. Hereby people convince others of the weakness and chaos among these groups, as well as legitimize the violent treatment of the jihadists.

Twitter users call on strategies to stop these groups. In reality, this may result in further ethnic and social segregation and armed violence towards them, without finding solutions for the conflict.

Twitter users call on strategies to stop these groups. In reality, this may result in further ethnic and social segregation and armed violence towards them, without finding solutions for the conflict.

It has become clear that memes in the Malian Twittersphere are a form of warfare. The tendentious discourses that lay at the base of memes have to be seen in light of the increasing amount of conflicting information in the overall mediasphere. People use visual creativity to make ideological arguments and change nuanced information.

Due to the shared characteristics like humour, replicability, and simplicity, memes are a unique format for people to make these messages attractive, while trivializing the violence that comes along with it. Hence, memes are not an innocent visual piece of culture. A ‘memedia war’ may have real-time implications.

Written by Luca Bruls

Bibliography

Al-Rawi, Ahmed. 2021. ‘Political Memes and Fake News Discourses on Instagram.’ Media and Communication 9 (1S2): 276–91. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3533.

Antinori, Arije. 2021. ‘Memetic Warfare, the dark irony that may become terrorism’. Formiche.net. 10 February 2021. https://formiche.net/2021/02/memetic-warfare/.

Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gal, Noam. 2018. ‘Internet Memes.’ The SAGE Encyclopedia of the Internet. Edited by Barney Warf. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 529-30.

“Memetic Warfare Archive,” About, Accessed March 23, 2022, https://densitydesign.github.io/teaching-dd15/course-results/es03/group03/about.html.