Master student Chiara Cozzatella and Research Master student Pieter Roden wrote a blog as part of a course at Leiden University.

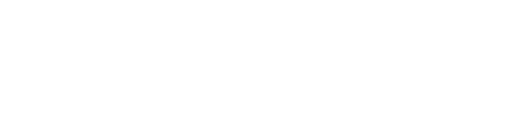

In this research project we aimed at understanding how the recent Tigrayan conflict is portrayed via TikTok. The short-form audio-visual content and young audience of TikTok provide an interesting insight into the conflict. Despite this there has been little academic attention on TikTok, conflict, and Africa, we therefore set out to understand the narration of the Tigrayan conflict on this platform.

The Tigrayan war was a complex media war, which occurred not only on the ground during the fighting, but also through social media responses and engagements that took place internationally. During the war, access to electricity and internet was reduced and at times entirely switched off (Fisher 2022). Humanitarian aid workers and journalists struggled to enter the region and information regarding the conflict was scarce and incomplete, particularly for external actors. According to Jonathan Fisher (2022), the Ethiopian state’s draconian interventions wield immense power and control over the region, insurgencies can also wield a level of control but “to a lesser extent in the case of Tigray” (ibid., 29). Through his discursive framing, Fisher contends that the Ethiopian state holds “an unparalleled advantage, at least at times, in curating and managing external perceptions of the crisis” (ibid.). Thereby Fisher’s research shows that part of the war has been the Ethiopian state’s ability to control the external narrative. Jan Abbink (2021a, 2021b) contends an alternative position. He argues against there being a distinctly anti-government attitude, particularly within Western responses. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that the coverage of Tigrayan war is marked by bias, incompleteness, lack of contextual understanding and credulity. A form of misinformation which he contends has spread from social media sources into wider platforms.

Abbink and Fisher’s diverging positions reflect how conflicting information and partiality regarding the war have spilt into academic debate. The informational contestation also spreads across platforms. In this blog, we aim to interrogate this conflict of misinformation and partiality. We hope to avoid, as much as possible, narrating a particular opinion or partiality on the war, highlighting instead the contestation of information. Through a pilot study on TikTok, we hope to explore the extent to which the growing usage of this social media platform plays a role in the creation of these conflicting debates. We aim to understand the role platform users play, exploring how it is that they, in the words of Fisher, may “reinforce the positions of the respective belligerents, making peace… a more distant prospect” (Fisher 2022, 28). In this blog we seek to answer the question: how does TikTok fit into the landscape of The Tigrayan media war?

During research we focused on the representation of the Tigrayan conflict from an exclusively Tigrayan perspective. This undoubtedly resulted in a limit to the study but, at the same time, it enabled us to show a peculiar side of TikTok, where diasporas are significantly active. We partly made the choice because of the high prevalence of this specific kind of content.

The Tigrayan conflict

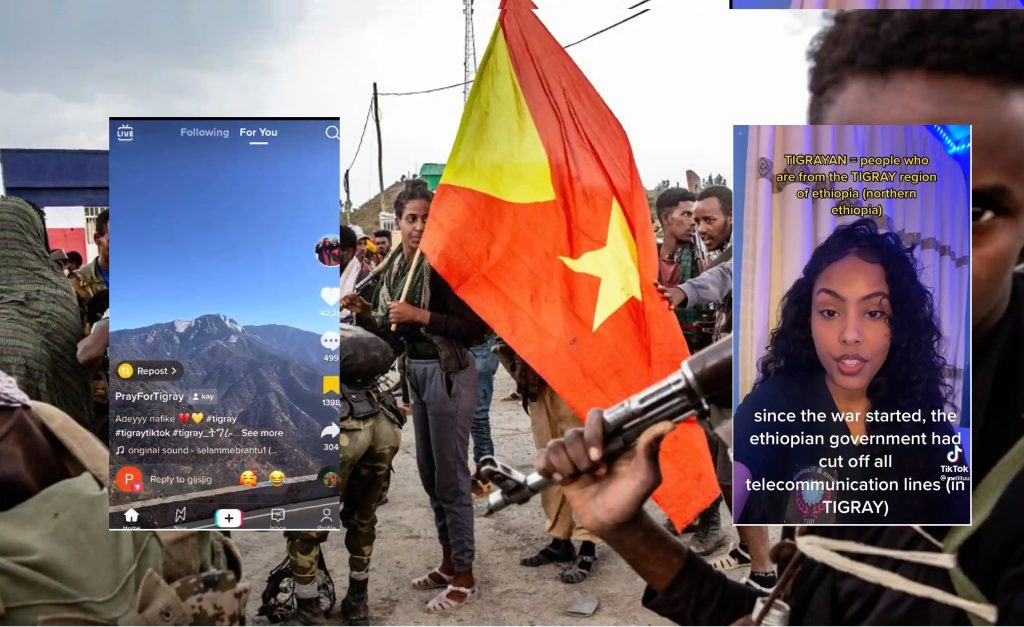

Since 1991, Ethiopia has been run through an ethnic federal constitution where the eleven Ethiopian regions are all allowed high levels of autonomous rule. This system was implemented following ethnic violence and oppression under previous regimes. Under the new constitution, the government divided each region through an explicitly ethnic framework and reference, thereby allowing as many rights as possible to the ethnic groups in the country. Tigray is one such region, home to the Tigrayan ethnic group.

Image 1 – Timeline

Image 1 – Timeline

The Tigray conflict erupted in November 2020 as tensions grew between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a political party leading the Tigrayan regional government, who had up until 2018 also ran the central government; and the new Ethiopian central government, led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, of Oromo ethnic origin. The current Ethiopian government is the first government to be led by a non-Tigrayan since 1991. The central government had postponed elections amidst the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequently refused to recognise the elections held by the TPLF. Amongst these simmering tensions, fighting broke out after TPLF forces attacked a significant Ethiopian government military base. In November 2022, the government and Tigrayan forces came to agree on a peace deal which has allowed a fragile level of peace to return to the region.

Mobile phone and social media use in Ethiopia

Digital connectivity is on the rise in Ethiopia, but access to internet and use of social media remains limited. The majority of social media users are located in urban areas. In rural areas, mobile phone use is significant, but access to stable electricity or Internet is rare. Dependent on older phone models, TikTok is barely present in rural Ethiopia. Our research indicates that TikTok is primarily on the rise amongst the Ethiopian diaspora and wealthy urban communities. Influence of diaspora communities is widespread and well-known, but interestingly new social media are bringing forward innovative networks of diasporans. In the virtual common space of TikTok (TikTok Cultures Research Network 2022), diasporans can discuss a variety of issues without the necessity of physical settings.

Image 2 – Connecting Africa phone data (Gilbert, 2021)

Image 2 – Connecting Africa phone data (Gilbert, 2021)

Tigrayan TikTok

We conducted research between November and December 2022, creating two TikTok profiles and started following popular profiles which published content on Tigray and the conflict. We focused on the entire TIkTok user interface, including video, audio, hashtags and comments to explore the narratives on Tigray and the conflict. Overall, we found a lack of rightful information of the war, which scholars and international organizations like the UN also claim (Abbink, 2021a). For this blog we present an analysis of two distinct TikToks we identified during this period. Additionally, we created a comment-map of the top 100 comments of each TikTok to understand their audience reception.

TikTok 1 – Dancing Soldier

This TikTok video features Merkeb Bonitua, a Tigrayan hip-hop artist who is politically active in the region. The interplay of military and artistic references is striking. The combat gear, TDF military beret, the saluting while dancing or playing the krar is comical, despite the darker undertones of war and conflict. The perspective taken in this TikTok video is clear: #tigraywillprevail. The pro-Tigray hashtag has over 218.5K views, and is used alongside the hashtags: #tigraytiktok, #Tigray_ትግራይ. #merkebbonitua, #hellog, #tigraytiktok, #Tigray_ትግራይ, #tigrayadey, #viral, #fyp, #follow.

Comments on the TikTok

ሀሉም ነገር እኩ በትግራዋይ ነው ሜያምረው (Everything is beautiful in Tigray)

ምድረ ለማኝ ሁሉ ከጠፋችሁበትተ ጉድጓድ ወጣችሁ አይጦች ናችሁ (You are mice out of the pit where all the beggars are lost)

the only ppl who I knw that dance on their defeat

tdf forever

Image 4 – Wordmap Dancing Soldier

Image 4 – Wordmap Dancing Soldier

The above comment-map of the top 100 comments shows audiences use English and Amharic words interchangeably, demonstrating a mixture of international, Ethiopian and Tigrayan audiences. Many comments refer to Tigray itself as ‘the Adey’, a yellow flower which emerges in the new year, signifying new life and a new beginning. Opponents’ comments are however also noticeable: the word defeat appears together with a derisive “game over” and “rip Tigray”.

Spreading information on the conflict: #Tigraygenocide

TikTok 2 – Information on conflict

This TikToker takes a different tone. Her explanation of the conflict is emotionally involving and takes on an informative tone. She is mainly addressing the non-Ethiopian world, identifying herself as part of the Tigrayan diaspora. She talks about the war, attacks the Ethiopian government, and stresses the crisis inside the region, her voice breaking when talking about starvation in the region. The TikTok video concludes with a request to make the hashtags #Tigraygenocide and #stopwarontigray viral. This user is also part of a collective group of Tigrayan diasporan TikTokers, that started a particular movement, #RestoreMotherland, to raise funding for the education of children in Tigray.

The first hashtag used is #tigraygenocide, a hashtag with over 32 million views. Abbink (2021b, p.4) contends #tigraygenocide to be “a meme recklessly used and repeated time and again but incorrect in the juridical and actual sense”. Abbink suggests some Ethiopians launched claims of genocide even in the first 24 hours of the conflict, so as to influence media and policy campaigns amongst the West (ibid.). It is certainly worth acknowledging that atrocities against civilians have been evident since the beginning of the conflict. The issue of genocide is particularly complicated in a highly violent contexts of war such as the Ethiopian one, as in different discourse types, settings and spaces, genocide comes to have different connotations. In academic settings there may be more focus on the “juridical and actual sense”, as claimed by Abbink (2021b, p.4), while social media circles operate through a different, yet nonetheless significant, logic of injustice and violence. TikTok as a platform comes to play a role in blurring these different connotations, definitions and understandings of genocide, through its audio-visual instantaneous presentation style. The interplay between these different settings, and the impact of the exchange of these different meanings certainly requires further research (Ibreck & De Waal, 2021).

Comments on the TikTok

what can we do to help

Why am I just hearing about this

#tigraygenocide what’s y’all’s favorite pizza topping?????!?!!?

BOOST: what’s y’all’s favorite color? Mines yellow

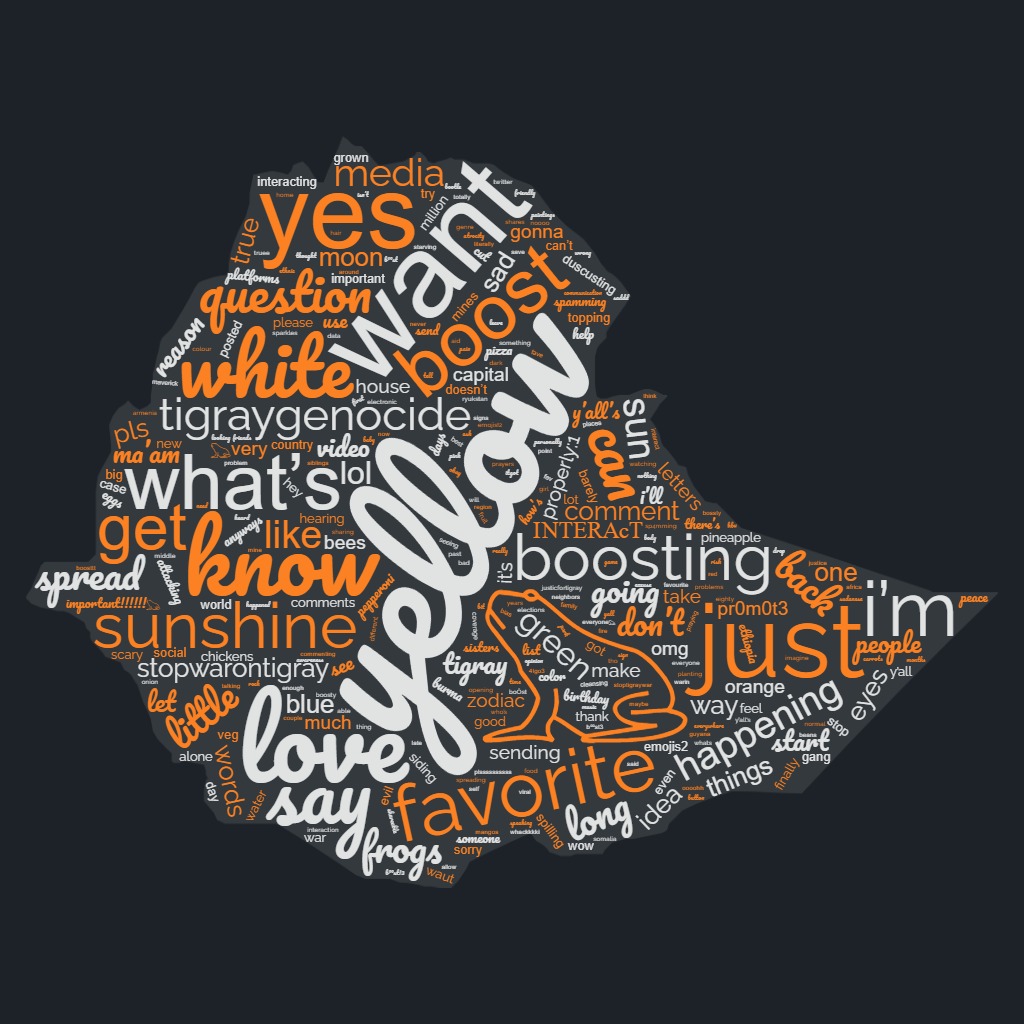

Image 5 – Wordmap Genocide Information

Image 5 – Wordmap Genocide Information

In this comment-map, all words are English. Notably words such as ‘boost’, ‘know’, and ‘yellow’, appear frequently, as well as the figure of a frog. These comments are explicitly aimed at increasing the virality of the TikTok, spreading its influence by using key viral words or by spamming.

We found that TikTok plays an active role in influencing partial and biased media war narratives, engaging in ethnonationalist discourses through its multi-media format. In the instances of the two presented TikToks this is through incorporating distinctly pro-Tigrayan visual imagery and music. ro-Tigray narratives are expressed through visual imagery which includes the Tigrayan star, soldiers uniforms, as well as music and sound which propagates Tigrayan patriotism and a strong individual identification with Tigrayan people and the region. At the same time, the narrative on the Tigrayan conflict largely remains a youth diasporan phenomenon. Additionally, hashtags such as #TigrayWillPrevail, #StopWaronTigray and #TigrayGenocide place Tigray into an underdog position, casting all responsibility for the war onto the Ethiopian government

TikTok’s easy accessibility makes it engaging for a wide range of users but particularly younger audiences. In the case of the Tigrayan conflict, TikTok comes to facilitate a particular exchange of information between Western communities and African diaspora, both of which are far away from the front-line of conflict. Content is therefore based on a lack of verifiable information. It is therefore a platform which is capable of harbouring warring sentiments, propagating misinformation or developing ethnonationalist discourses which exist in other platforms. TikTok usage in this way reflects, repeats, and develops wider societal discourses through a distinctly audio-visual format. In this blog, we focused exclusively on Tigrayan self-representation, exploring how young Tigrayans speak up and create dialogues and communities. The online spaces of TikTok allow for the creation of many different discourses, from funny musical memes to sharing and connecting serious matters. We thus encourage researchers to continue venturing these topics on TikTok.

Written by Chiara Cozzatella & Pieter Roden

Bibliography

Abbink, Jan. 2021a. “The Atlantic Community mistake on Ethiopia: counter-productive statements and data-poor policy of the EU and the USA on the Tigray conflict.” ASC Working Paper, 150 no. 2: 1-30.

Abbink, Jan. 2021b. “The politics of conflict in Northern Ethiopia, 2020-2021: a study of war-making, media bias and policy struggle.” ASC Working Paper Series, 152: 1-24.

Anderson, Katie Elson. 2020. “Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: it is time to talk about TikTok.” Library Hi Tech News, 37 no. 4: 7-12.

Fisher, Jonathan. 2022. “#HandsoffEthiopia: ‘Partiality’, Polarization and Ethiopia’s Tigray Conflict.” Global Responsibility to Protect, 14: 28–32.

Gilbert, Paula. 2021. “Only 20% of Ethiopians are online.” Connecting Africa, March 15th 2021. https://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761&doc_id=768066

Ibreck, Rachel and Alex de Waal. 2021. “Introduction: Situating Ethiopia in Genocide Debates.” Journal of Genocide Research, 24 no. 1: 83-96.

International Organization for Migration. 2022. “Global Diaspora Summit Background Note Session 6 – Digital Diaspora: Technological Tools for Engagement.” Global Diaspora Summit. [Online] Accessed via: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/inline-files/session-6-digital-diaspora-technological-tools-for-engagement-.pdf (01/02/2023)

TikTok Cultures Research Network. 2022. TikTok & Asian diaspora recordings, Roundtable Event October 25th 2022. [Online] Accessed via: https://tiktokcultures.com/tiktok-and-asian-diaspora-recordings/